Earlier this week, I published an article on Forbes.com titled "Here’s Why Climate Change Is Actually Not an Existential Risk.” (The original title was “The Nonsense Narrative Of Climate Change As An Existential Crisis.” My editor changed the title but did not change the content.) What motivated the piece was a very recent paper “The Science vs. the Narrative vs. the Voters: Clarifying the Public Debate Around Energy and Climate” by Roger Pielke, Jr. and Ruy Teixeira of the American Enterprise institute (AEI). The paper is based on a survey of over 3,000 voters that was conducted for AEI by YouGov between September 20-26, 2024. If you haven’t read this paper I encourage you to do so.

I posted my piece on LinkedIn, where it generated 45 comments, the vast majority of which were negative. As I read through the responses, I found myself confronting an uncomfortable irony. While my piece critiqued climate advocates for potentially alienating broader audiences with their messaging, my own approach may have alienated the very climate experts whose engagement we desperately need.

I should also say that some of the comments were rather vituperative and a few bordered on ad hominem attacks. Such is life in the social media world, even on LinkedIn 🐥. I will say more about this later but, more importantly, this experience offers a valuable lesson about the challenges of climate communication and the difficulty of building the broad coalitions necessary for effective climate action.

Eating Humble Pie

Let me start with some self-reflection. My piece was designed to speak to a general audience across the political spectrum, the kind of people who read Forbes and are concerned about climate change but not big experts on the topic. But in doing so, I used overly broad characterizations that cost me some credibility with climate experts and activists.

Several commenters legitimately called out my lumping together of very different figures. Nicholas Miller pointed out that "attributing a 'doomsday narrative' to all of the people you mention is not accurate. Al Gore always emphasizes that we already have all of the tools to address the problem but are lacking the political will." He's right. My characterization was unfairly reductive.

Similarly, Keith Nelson accused me of "making a show of trashing a strawman depiction of climate activists," arguing that I was reducing complex organizations to "absurd and simplistic arguments." While I disagree with his accusation of insincerity, his point about oversimplification has merit.

Alan Calcott observed that “I agree with some of what you say in the article Robert Eccles … but at each point where I start agreeing with you you throw in a looney leftists or fossil haters type opinion … and in the end I disagree with both your opinions and conclusions.” If I’m losing people who agree with me, that is valuable feedback to have.

Matthew Archer made perhaps the most pointed critique of my framing: "'Singularly unhelpful' is a strange way to describe a small group of Western activists and politicians who are trying to promote policies they believe will make the world a better place in the future. The fact that they are engaged in this struggle implies that they are the exact opposite of doomers or catastrophists; it means they have hope!"

These critics are correct that my language—phrases like "singularly unhelpful" and "nonsense narrative"—was more dismissive than constructive. If I want to encourage broader public debate, I should model the kind of nuanced engagement I'm calling for.

The Irony Reveals Itself

But there’s something else worth pointing out. In critiquing my approach for potentially alienating audiences, many commenters proceeded to respond in ways that might alienate the very broader audiences I am trying to reach. The irony is almost poetic. I wrote about how climate discourse struggles to speak beyond its core constituency, and the response largely proved the point.

Consider John G.'s repeated dismissive comments about my "fallacious arguments" and wondering if my upcoming book will be "as far off-the-rails as B. Lomborg." These responses, while perhaps satisfying to write, hardly model the kind of inclusive discourse that might persuade skeptical audiences. Still, as I have already acknowledged, I didn’t model that in how I portrayed some climate activists.

This dynamic—where strategic critiques get treated as attacks on the cause itself—may be part of why climate advocates struggle to build broader coalitions. When even internal discussions about messaging effectiveness trigger defensive responses, it suggests a movement that may be more focused on maintaining ideological purity than building political power. Let me be clear. I don’t think we can build the political consensus we need in a very polarized America unless we can garner broad public support. Some of the angrier comments are part of the problem I’m trying to address, where I admittedly need to do better.

Five Major Themes in the Pushback

The 45 comments fell into five major themes, each revealing different aspects of our climate communication challenges:

1. Questioning Ecoright Effectiveness

Multiple commenters, including Andrew Winston (who I know and for whom I have a great deal of respect), James Boyle, and Thomas Odenwald, challenged whether conservative climate organizations are actually effective. Winston asked pointedly: "no national level republicans have voted for any form of climate action or support for the clean economy in years. Not a single vote for IRA for example. So what is this eco right actually doing?"

This criticism has merit, but it also reveals the scale challenge these organizations face, which I'll address below.

2. Disputing My IPCC Characterization

This generated the most technical pushback. Young-Jin Choi provided detailed citations arguing that "the IPCC does not associate climate change with existential, apocalyptic, or catastrophic outcomes" is "simply not correct." He quoted AR6: "Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health. There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all."

James Boyle went further, citing specific IPCC reports about tipping points and arguing that "AR6 WGII tightens this, stating explicitly that the transition to high risk [!!] for Tipping begins between 1.5 °C & 2.5 °C."

These commenters are largely correct on the technical details. The IPCC does discuss severe risks, though it typically uses scientific rather than popular language. My characterization was overly simplified. But here’s the challenge. As soon as I start getting into the technical details, I’m losing the broader audience I’m trying to reach. That I hope my critics want to reach as well. Plus, in a post on Forbes.com there is only so much space I can devote to any particular issue.

Furthermore, I do not downplay the consequences of climate change, and I acknowledge the existence of tipping points. My point was that “the end of the world” narrative is not an effective way to mobilize most American citizens, and I provide statistics and reasoning for that. Those taking issue with my characterization are basically doubling down on this narrative.

Similarly, very few commenters engaged with my argument about needing stable, bipartisan solutions. Most treated this as a typical partisan debate rather than recognizing that durable climate policy requires broader political coalitions than we currently have.

This pattern, where strategic critiques get treated as attacks on climate science itself, may explain why climate discourse often feels like an echo chamber, and why the movement struggles to adapt its approaches based on empirical feedback about their effectiveness.

3. Defending Climate Activists

Many commenters pushed back on my "doomsday" characterization. Gabriel Mauger argued: "What you present as the « doomsday narrative » seems only to be the description of the risks we are facing if we continue on the same path. Warning the public about the risks that are clearly and scientifically documented is not being doom but being realist." He also rightly noted that “What new narrative are you suggesting ? It is not clear from your article. I don’t think it is a good way forward to try antogonising different approaches which could be complementary.” In fairness to me, the piece wasn’t intended to be a new narrative, but I will be offering one in my book “An American’s Guide to Climate Change: How America Can Lead and Prosper” which will be published early next year.

I hope it will address the sophisticated argument made by Alice Kalro that, "Narratives by definition need to be tailored based on what action they are meant to inspire, in what audience. And their effectiveness to be assessed based on whether mobilisation towards action is taking place, in that audience."

4. Current Impacts as Present Reality

Several commenters emphasized that for many people globally, climate impacts aren't future scenarios but current realities. Jury Gualandris noted: "For several in the world, more often in southern countries and in lower social classes, doomsday is a daily reality, not a distant possibility."

Bill Stough made this personal: "please tell the millions of people whose lives will never be the same because of the deadly impact from prolonged extreme heat events... that the world as they knew it has not changed."

This is perhaps the most compelling pushback to my argument. The challenge is how to acknowledge current suffering while still building broader political coalitions. This is a very difficult challenge. As a practical matter, and some of my critics won’t like this, emphasizing this point is not something that will mean much to the broad American public. While I am well aware of the fact that climate change will have the greatest impact on those most vulnerable to it, my focus is trying to find a narrative that includes the largest possible range of the political spectrum in a highly polarized country—on climate and a large number of other issues. Do I like this? Of course I don’t. But it’s a fact I must deal with since I can’t change it.

5. Messaging Psychology Complexity

Some commenters engaged more constructively with my core argument about messaging effectiveness. Dr. Ruby Campbell acknowledged that, "cognitive psychology researchers have shown that adopting a doomsday narrative can sometimes be counterproductive" while also noting that such narratives "have played a role in shifting the dial."

Jennifer Dudgeon found middle ground: "I completely agree with you. The Doomsday narrative isn't productive. However, I believe there's a delicate balance between being realistic about climate change and effectively motivating people to take action."

Putting the Ecoright Into Perspective

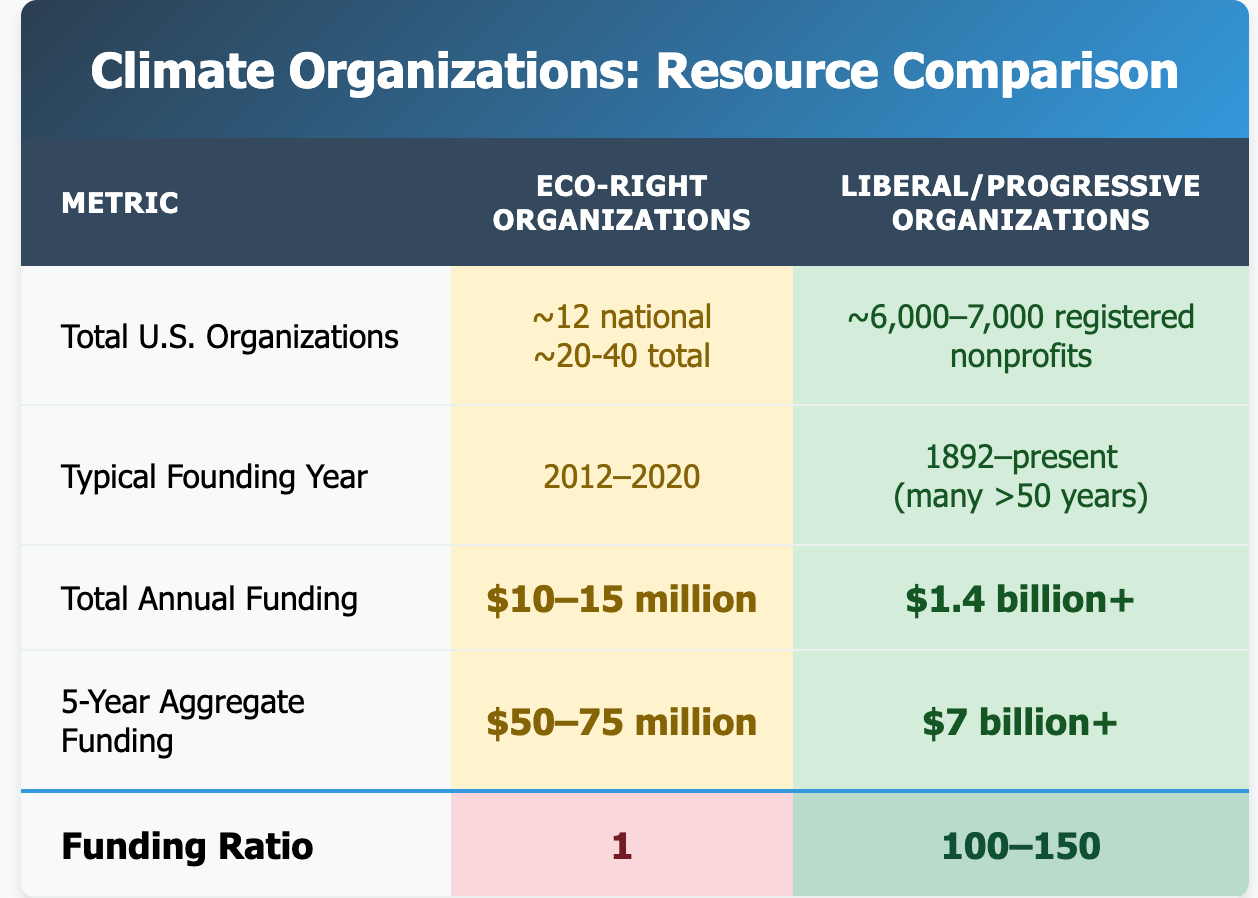

As noted above, some commenters questioned the influence and effectiveness of the Ecoright. I mentioned the nine I know (Alliance for Market Solutions, American Conservation Coalition, C3 Solutions, Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions, ClearPath, Climate Solutions Fund, DEPLOY/US, RepublicEN, and the R Street Institute) and there are a few others at a national scale. All of these organizations are new, around 10 years old at best. It is instructive to compare the Ecoright to NGO climate activity on the left.

The total annual funding for all Ecoright climate organizations combined is approximately $10-15 million. Individual organizations operate on budgets ranging from several hundred thousand to a few million dollars annually; CRES Forum runs on about $3-4 million per year, American Conservation Coalition on roughly $2 million, and ClearPath on $5-7 million.

Sources: The Chronicle of Philanthropy, "The 'Eco-Right' Is Growing. Will Bipartisanship Follow?" (May 2025); E&E News, "Who funds conservative green groups?" (June 2024); Foundation Directory Online; Climate and Capital Media sector reports (2024-2025); organizational IRS 990 filings.

Now compare this to their liberal counterparts. There are an estimated 6,000-7,000 registered environmental NGOs in the United States (about 500 times as many compared to the Ecoright), with the major national players operating on vastly different scales: Sierra Club ($100-120 million annually), Environmental Defense Fund ($180 million), NRDC ($140 million), League of Conservation Voters ($40-60 million), and Greenpeace ($60 million). These organizations have been around for decades—Sierra Club since 1892, EDF since 1967, and NRDC since 1970.

The funding disparity is staggering. According to Foundation Directory Online and climate sector reports, environmental groups received over $1.4 billion in philanthropic funding in 2022 alone, with conservative climate organizations receiving less than 1% of this total. The funding ratio is at least 100:1, possibly closer to 150:1. To put this in perspective, what the entire Ecoright field receives in five years ($50-75 million) is at best 25% of what just EDF and the Sierra Club together spent in 2022 ($300 million).

So when Andrew Winston asks, "what is this eco-right actually doing," I'd respectfully turn the question around. Given these resource disparities, shouldn't we be asking what the massively better-funded environmental establishment has accomplished with their decades of work and billions of dollars in funding? If current polling shows that despite generations of advocacy and enormous financial resources, we still can't build broad-based public support for climate action, perhaps the critique shouldn't be directed at the tiny organizations trying different approaches with minimal resources.

Winston also mentioned that not a single Republican voted for the IRA. This is true. How many Democrats vote for Republican bills? And there are Republicans on record about climate change such as Senator John Curtis who started the Conservative Climate Caucus when he was a member of the House. It is now chaired by Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks and has 65 members, including 12 from Texas and five from Florida. They are not climate change deniers. They, like the Ecoright, simply have different ideas of how climate change should be addressed. Several years ago I wrote about the different views conservatives have about how to address the challenge of climate change.

For sure the right has been slow to the table when it comes to climate change. One result of this, and we’re all paying the price for it, is that climate change has become a liberal issue and entangled with other liberal causes. But now that conservatives are showing up shouldn’t we be engaging with Ecoright organizations and Republicans in Congress who are concerned about climate change, rather than berating them for not doing more in an environment with an administration that is ideologically and irrationally hostile to the very notion of climate change? And, by definition, engagement doesn’t mean trying to convince them your answers are better than theirs.

The Challenge Back

While I found many of the critiques helpful for improving my own thinking, I want to pose a challenge back to my critics. What's your strategy for building broader public support? Very few commenters engaged with my argument about needing bipartisan solutions and simply treated the issue as a partisan battle. Exceptions to this were:

· Elizabeth Doty (“Thank you for clarifying and everyone should read Glacial by Chelsea Henderson!!!! https://www.amazon.com/Glacial-Inside-Story-Climate-Politics/dp/1684429579 “)

· Jennifer Dudgeon (“I completely agree with you. The Doomsday narrative isn't productive. However, I believe there's a delicate balance between being realistic about climate change and effectively motivating people to take action.”

· R. Paul Herman (“66% of Trump voters and 77% of Americans agree that there are climate tipping points as scientists have analyzed. So we need more climate action, and we need leaders who understand we need more climate action! “)

· Tamara Somers (“I don’t agree with everything you suggest but I really welcome you opening up the debate in this way.”)

· RepublicEn ("At republicEn, we agree that durable climate solutions require broad public support across the political spectrum—not fear-based messaging that alienates people. The survey underscores what we've long seen: many conservatives acknowledge climate risks but are looking for practical, market-based approaches, not doomsday rhetoric.")

Most of the comments focused on defending existing approaches or correcting my technical characterizations. Some commenters seemed to suggest that more accurate scientific communication is the answer. But if that were true, wouldn't we have solved this problem already? The IPCC has been producing increasingly detailed and alarming reports for decades, yet public support for aggressive climate action remains limited.

Others seemed to suggest that current messaging approaches just need more time and resources. But again, if that were true, wouldn't the billions already invested in climate communication have produced better results?

A few commenters, like Alice Kalro, as noted above, engaged with the strategic question more directly, noting the need to tailor narratives based on target audiences and desired actions. But even these responses didn't grapple with the specific challenge of reaching audiences beyond the already convinced.

A Question and An Offer

This brings me to a very pointed question. Are some climate advocates so invested in current approaches that they're closed to strategic discussions about alternatives? Several comment threads revealed a pattern where any critique of messaging strategy got treated as an attack on climate science itself. When I argued that "doomsday narratives" might be counterproductive, multiple commenters responded as if I were questioning the reality of climate risks rather than the effectiveness of communicating about them. This dynamic may explain why climate discourse often feels like an echo chamber. If strategic critiques are treated as heretical, how can the movement adapt and improve its approaches?

Steven R. Smith made a nuanced point that illustrates the challenge: "The evidence on fear as a motivator is much more complex than you state. It can be highly motivational in some contexts. Most people can accept the possibility of civilisational risk without shutting down or thinking Doomsday is inevitable. The most important thing is that people believe there are achievable solutions - which there are." This kind of sophisticated thinking about communication psychology is exactly what we need more of. But it requires being open to questioning current approaches and experimenting with new ones.

Thus, I'm encouraged by commenters like Elizabeth Doty, who wrote: "Maybe we are ready now for their solutions." And Tamara Somers, who noted: "I agree this is a conversation we need to have, and not just in America. We need broad-based support for the energy transition... I think it's possible to have a more nuanced public discussion about this than the current one."

These responses suggest there's at least some appetite for the kind of strategic conversation I was trying to start, even if my initial approach was flawed.

So let me end with an offer. I can have guest writers for my Substack newsletter. If anyone would like to write a piece offering up their ideas for creating broader public support to get bipartisan policies to address climate change, I’d be more than pleased to publish it. I’ll give you feedback on a draft but the final content is totally yours. You don’t have to completely agree with me. You can even mostly disagree with me. All I’m asking for are thoughtful arguments for how to bridge the partisan divide.

Bob, I stand with you shoulder to shoulder.

I did not see your LI post (probably don't need to now, given your excellent exec summary!)

I was planning to comment on LI, but as I reached your offer, I moved to Plan B. Off to draft a piece which i will send to you by email for critique, and see where we go.

I appreciate your effort to reach out to those aligned with the political right in America who are open to or actively engaging in climate action. You are correct that building a broad coalition will be necessary to make real change.

If I can suggest a possible explanation for the defensiveness of those on the left, I suspect a fair amount of this stems from distrust borne out of the perception of fossil fuel companies (and, by extension, those who support them politically) as intentionally misleading the public regarding the harmful effects of their products on the environment. Merchants of Doubt by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway comes to mind.

I can imagine it to be difficult to convince a left-leaning climate activist to trust the intentions of an Ecoright proponent if they grew up with this perspective, especially if the Ecoright proponent's solutions are more similar to the status-quo than their own. It may come across as greenwashing or some other manipulation.

Let's hear more voices advocating for a narrative of a better future we can all contribute to making into reality.